Kyle’s humor is delightfully dry, occasionally dark, and always stunningly candid.

“I used to be so rude to myself—just to be funny,” they recounted. “I would joke that I must just be a broken human. Then somebody told me, ‘I wish I’d gone through the same things as you because you're really funny.” And I stopped, looked them right in the eye, and said, ‘No. No, you don't.’

Kyle was only 8 years old when the abuse began.

“It started when I was 8, but it continued for five years because I didn't understand,” they said. “Like, What's going on? Is this just some weird form of playing? But no; it was something much more sinister.”

They didn’t learn the sinister thing’s name until their first high school sex education class at age 13. “That happened to me,” they remembered realizing.

Kyle was subjected to this last type of abuse: sexual abuse by a family member, otherwise known as incest.

“My abuser was my half-brother,” Kyle bravely disclosed. “I knew he was different. There was something wrong, you know? He was into a lot of illicit drugs.”

The half-brother’s drug use was known to the children’s parents, who repeatedly tried various interventions. Meanwhile, the sexual abuse persisted, undetected, year after horrifying year.

“He was five years older and much stronger than me,” Kyle described. “We slept in the same room, and it got to the point where I wasn't sleeping. He would terrify me, telling me that if I said anything to anybody, he would hurt me and he would hurt my parents. The threat felt so real, I decided, I better keep quiet.”

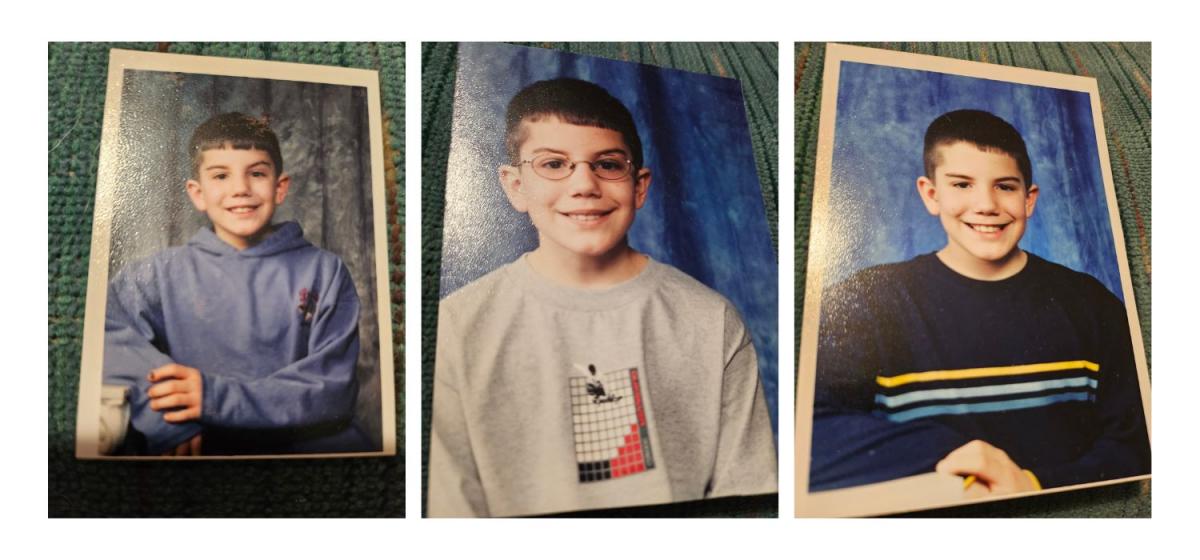

Left and center: Kyle in school portraits taken before the abuse began. Right: Kyle in a school portrait taken after the abuse began. Photos courtesy of Kyle G.

Asking for Help

Kyle identified the abuse for what it was at age 13, but three more years passed before they disclosed to anyone in a position of authority.

“At 16, I went to the guidance counselor at my school—and it wasn't by choice,” they said. “I had a breakdown because I was still struggling with the aftermath of the abuse. It was affecting my relationships. And once I told the counselor, they told my mother.”

"Educators are mandatory reporters, meaning they are obligated to report suspected abuse to either law enforcement or the state," explained RAINN Senior Manager of Consulting Mara Noel White (she/her), LMSW. "They don't need proof that the abuse is happening; gathering evidence should be left to the authorities."

Initially, Kyle felt hopeful. “My mother kind of hugged me when I got home, and she said, ‘It's okay. We're gonna get you the help that you need, and everything will be all right.’”

But then his mom added, “Just don't talk to your dad about it. He's very upset, and you'll just make him angry.”

Another year dragged by. Finally, Kyle worked up the courage to ask his mom about the promised visit to a doctor. “She was the person that I trusted to take care of me, but all she said was, ‘Well, Kyle, I don't know what to tell you. It's expensive.'"

When a child or teen tells an adult they're being abused, the adult should first listen to what the young person is saying, thank them for their trust, and then do their best to describe what will happen next.

– MARA NOEL WHITE (she/her), LMSW, RAINN senior manager of consulting

With his parents’ relationship in turmoil and no help on the horizon, Kyle moved out.

“I lived in my Jeep in the school parking lot,” they shared. “I would normally say that’s a terrible thing, but I actually loved it because I was safe. I could lock my doors and wrap myself up in my comforter and do my homework. My grades were good! Nobody had any reason to suspect that I was doing this—until they finally caught me on a security camera.”

In an unexpected act of compassion, the school’s principal invited Kyle to live with him and his wife for a while, but the offer felt like a risk to the teen’s hard-won sense of safety. For a time, Kyle did live with his girlfriend’s family, but that proved to be an unsustainable solution.

Out of options, Kyle enlisted in the Army—a guaranteed path to college—and began basic training in September 2010.

“At first, it really wasn't bad,” he admitted. “I liked it. I had structure. I had rules to follow. And it helped me grow up even more than I had.”

But the lack of privacy inherent to enlisted life took its toll on Kyle, as did the base’s widespread problem with stealing. When an important tool disappeared from his locker, a sudden flood of fear “compounded and cascaded until I thought I was having a heart attack,” Kyle described. “They were checking my pulse and I was grabbing at their arms, like, I'm dying. I’m dying. I’m dying.”

In fact, Kyle was having their very first panic attack.

At the hospital, a psychologist asked, “Is there any reason you would have anxiety? Is there something you're not telling us?”

When Kyle revealed his abuse-filled childhood, the doctor dealt another devastating blow: the young Army recruit was medically disqualified.

Finding a Way Forward

“When I left the military, I felt like I had failed,” Kyle revealed. It was 2012, and nothing was going the way they’d hoped.

“I was drinking a lot—trying to self-medicate. Things were so bad, I thought, I wish I could just fall asleep and never wake up again.”

But Kyle did wake up, morning after morning, and did everything they could to keep moving forward.

“Say you have a glass with a hole in the bottom. You know there's a hole there, but you just keep pouring liquid into it, wondering why it won't fill up. That's what I felt like for so long.”

Kyle was 28 years old when he finally went to therapy. “I’d spent 15 years hitting my head against a wall, thinking, This wall has gotta give, eventually… Then suddenly I had someone knocking on the other side of the wall, like, ‘Hey! Just go through the door!’”

For Kyle, the person who made the biggest difference was a therapist named Stephanie.

Photo courtesy of Kyle G.

“After our first appointment, she asked, ‘Kyle, what do you want more than anything?’

I said, ‘I just want to sleep. Like, I want to lie down at night and just go to sleep.’ And she said, ‘Then that's our first step.’

“I hadn’t even known what I wanted before then,” he said. “Nobody had ever asked me. I didn't even ask me!”

Session after session, week after week, Kyle and Stephanie worked together to build a bigger, more effective toolbox of coping skills that were conducive to healing.

Kyle explained. “I started facing the multiple things that had happened to me and understanding, Yeah, it was bad. And YOU SURVIVED IT.”

Healing In Community

Numerous studies demonstrate how the lasting effects of sexual violence hinder an individual’s ability to create healthy interpersonal relationships—yet healthy human-to-human connections are vital to a survivor’s healing process.

Kyle remembers the years spent “craving human connection. Whatever I could do to people-please, I’d do it. But I had to stop; I was giving so much of myself away, I had nothing left for me.”

In that space of self-love and resilience, Kyle met his new coworker, Vanna—and she wasn’t having a very good day.

“She had her headset on and her hood up—I should have taken the hint.” Kyle shook his head. “But I went over and gently put my hand on her desk, and she stopped her music and just looked at me, confused. I said to her, ‘Hey, we're gonna get through this!’ But she just went—” Here, Kyle mimicked Vanna’s response: one middle finger raised defiantly skyward. He grinned. “Three months later, we started dating!”

Kyle and their partner, Vanna. Photo courtesy of Kyle G.

On their first evening out, Kyle took Vanna’s hand and said, “I'm gonna tell you about all of the skeletons in my closet. If it's ever uncomfortable for you, let me know and we never have to talk about it again. But this is important to me.”

That same night, after hours of talking, Vanna told Kyle she loved him.

“That went miles for me,” Kyle said, “because I poured my heart out, and she not only accepted me but loved me.”

Other people’s words have a direct effect on your brain activity and your bodily systems, and your words have that same effect on other people. Whether you intend that effect is irrelevant. It’s how we’re wired.

– LISA FELDMAN BARRETT, neuroscientist and author of "Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain"

Despite repeated abuse during their formative years, Kyle had regained one of humanity’s most essential traits: the ability to establish a truly loving relationship.

“We respect each other's boundaries, but we also work to fix problems,” Kyle explained. “We understand that maybe my cup isn't full enough today; maybe Vanna’s isn't; but we use these terms openly, and that’s what’s given me the relationship I craved for so long.”

As Kyle learned and grew and healed, they discovered a desire to do something—to help other survivors. “I found RAINN and the RAINN Speakers Bureau, which gave me a space to talk about my experiences with the aim of helping others with theirs. I have no doubt that listening to survivors tell their stories has been instrumental to the progress I've made over the last five years.

“I have no doubt that listening to survivors tell their stories has been instrumental to the progress I've made over the last five years.”

“We know how many survivors are out here; we know the statistics; and I want to hear from more of them. I want them to tell their stories and go to therapy and get the help they need. The floor just has to be open for people to speak, and RAINN is giving that to survivors.”

Some days, Kyle still wonders, “In the universe of different paths, who is the Kyle who never had this happen to him? Part of me wants to know, but the other part of me is so happy with myself now. I feel like, This is who I am meant to be—even though what happened is so terrible. Because I'm alive, I’m healing, and I'm helping others heal.”

In their ongoing pursuit of healing, Kyle even determined to face their abuser in court—but the statute of limitations had passed.

“A lot needs to be done with the laws in our country,” he said emphatically. “I have physical signs of abuse that would prove my case, but I can't take it to anyone, and that's tough. If that opportunity does come one day, I'll be ready. And if that day doesn't come, I can live with that.

"That's the important distinction: I have to keep going. I have somebody who really cares about me, and I care about her, and I want to have a long life. That’s not something I ever wanted before.”

In late spring, Kyle and Vanna visited a local park and sat on a bench overlooking the city. As the sun streamed through the clouds and poured over the landscape, Kyle looked at Vanna and thought, Wow. This is actually really GOOD, isn't it?

“If life had to be summed up: It's here,” said Kyle. “It’s now. It’s putting all the heavy stuff down for the moment and just being present.”

Kyle and Vanna are engaged to be married in October 2024.

|

And if you need someone to talk to, contact RAINN. Our support specialists provide free, confidential, 24/7 support in English and Spanish.

|