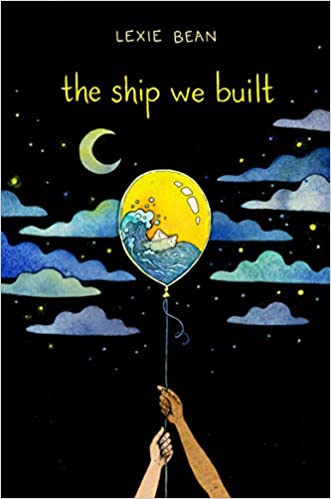

Author of New Children’s Book on Healing and Exploring Identity

In the just-released children’s book, The Ship We Built, author Lexie Bean tells the story of a transgender boy, Rowan, learning to embrace his own identity while healing from child sexual abuse. Based on the author’s own experiences, The Ship We Built tells a tender and nuanced story that can help children—and people of all ages—understand their own identities and how they can support others who are discovering theirs while healing. RAINN’s Christy Rozek recently sat down (virtually) with Lexie to learn more about their story as a survivor and author.

How did your experiences growing up transgender and as a survivor of child sexual abuse informed and shaped The Ship We Built?

Like Rowan, I was afraid of exploring my gender—even as an adult—because I was abused by primarily cisgendered men. I was afraid of emulating them or becoming the very thing that had hurt me and many others in my life. It's very hard to find role models as a young person being abused, and it's hard to know what to become as we continue to grow and change. Knowing I was both queer and trans compounded this.

Rowan in The Ship We Built has a very similar journey of doubt, grasping for connection, and relying heavily on the natural world and his own imagination to get by. Rowan also continues to question whether or not he could really be a boy because, in a binary society, he has internalized the message that "only girls get hurt." He doubts whether he is allowed to feel pain in order to be a "real boy." He doubts whether he could be a boy if he is being abused when the only way to talk about it within the public narrative is to claim girlhood (especially in my childhood and the book taking place in the late 1990s).

When Rowan begins to more visibly explore both his gender and queer sexuality, people are quick to label it as the thing that "went wrong" and should be fixed. It becomes an abomination instead of a celebration—meanwhile the sexual abuse continues to go unaddressed. An emergency is found in the wrong thing.

Based on my own experience, Rowan's father is especially quick to police his gender expression because of his own internalized homophobia in being attracted to someone who does not visibly identify as a girl. His hatred for Rowan grows during the day, and the "love," really abuse, stays the same at night. Rowan has nowhere to turn, as he's already being increasingly bullied at school and feeling further and further away from his own body and autonomy. He resorts to not speaking, or as I also called it at his age "the no talking game."

What advice do you have for young people who are learning about their own gender and sexuality while also healing from sexual violence?

You don't owe anyone an explanation or a reason for why you are the way you are. You have the right to take everything at your own pace. Your body is your own. You are complex and lovable at the same time. Your exploration of gender and sexuality is a normal part of growing up. Abuse should not be. And you can grow up to be something you've never seen before, and that may mean staying where you are and reinventing it or going somewhere entirely new. Every day you will continue to learn new things about yourself; treasure it, because it is a part of you.

In the novel, you show how Rowan’s teacher notices warning signs of child sexual abuse and offers support while also affirming him as he explores his gender. What are some other ways that teachers, coaches, or others in a young person’s life can support them?

When I was in elementary school, like Rowan, I stopped speaking. Perhaps because a part of me had given up. As someone raised as a girl, it was normal or cute to be "shy." Looking back, I don't think I was shy. I was trapped—and still have to navigate that feeling. I wish teachers and mentors took my silence more seriously, listened more, or offered resources. A small, but hugely impactful thing for young people experiencing abuse at home is activities, whether it be sports, the arts, or starting a club that offers a place to go instead of home after school—a place, even virtual, to look forward to and feel safe. Everyone needs at least one space to let their guard down, to smile, and not fear that they will be punished for it. For Rowan, these "safe places" are his secret club, ice skating, buying his balloons, and exploring the natural beauty of Michigan.

Listening, of course, is key. Even in silence. It's ultimately Mr. B's choice to speak the name Rowan has been using the most. It's his choice to offer Rowan a spotlight for his voice at the concert, even when Rowan doesn't think he is deserving of it. These gentle nudges are vital for a sense of self-worth and trusting that abuse is not inevitable or earned. Support does not need to be grand gestures—it is a series of small moments that string together into a new reality.

If my middle school and high school had been more supportive environments that offered resources or a place to go after school to continue exploring storytelling through writing, my life and relationship with my voice could have turned out quite differently. I wouldn't have spent so much time running from my gift or my truth, and they are one in the same. Even when I eventually went to college, I avoided any personal writing classes because I was afraid of getting in trouble or even being “wrong” about my experience. I feel the irony of sharing this as an author—but at times I still get overwhelmed by the feeling of getting in trouble for offering what I know instead of trusting that my story will simply be held.

What words of hope do you have for survivors, particularly children, who have had to quarantine at home with an abuser?

Hold what you can. A tiny rock that nobody else knows the meaning of, hold yourself until you feel your own embrace. Hold your reflection in the window closest to your bed. Write what you know into music, write what you know into coded words that one day will connect you to many others. Find your own version of stars. Try to find sounds that give you comfort, maybe the purr of a cat, the drip of your shower, or a scribbling crayon. Remember it's not your fault that anyone lost a job; it's not your fault that that someone is sick; it's not your fault that school may be confusing or hard; it's certainly not your fault any of this is happening right now. It's okay if you can't think of any good things right now, but when you're ready—they will be there waiting for you.

What would you like kids—and adults—reading this story to take away from it?

You do not have to go away for the world to be better. And continuing to release your metaphorical balloon—even if it only bears bad news, anger, loss, something that only feels real to you—is nothing to judge. There will always be something bigger than you to hold your thoughts, whether it be the sky; Gods, if you believe in any; or your body alone. Asking for help takes many forms.