Serial rapists continue to evade justice because states prevent juries from hearing about other similar assaults by the same person. The rules of evidence should provide survivors the opportunity to tell their stories, if they are relevant and probative, so that jurors can understand the true nature of the defendant’s criminal conduct. Changing states’ rules of evidence to align with existing federal rules of evidence for sexual assault sends a clear message: survivors are not alone, and rapists will not get away.

Amending the rules of evidence will not change the underlying rule that prevents information that is more prejudicial than probative, and will create a trial process that understands the unique nature of sexual assault crimes. States must pass a law that no longer privileges rapists at the expense of survivors. We urge lawmakers to make the justice process fairer by allowing the jury to consider all the evidence: change the rules of evidence to align with Federal Rule 413.

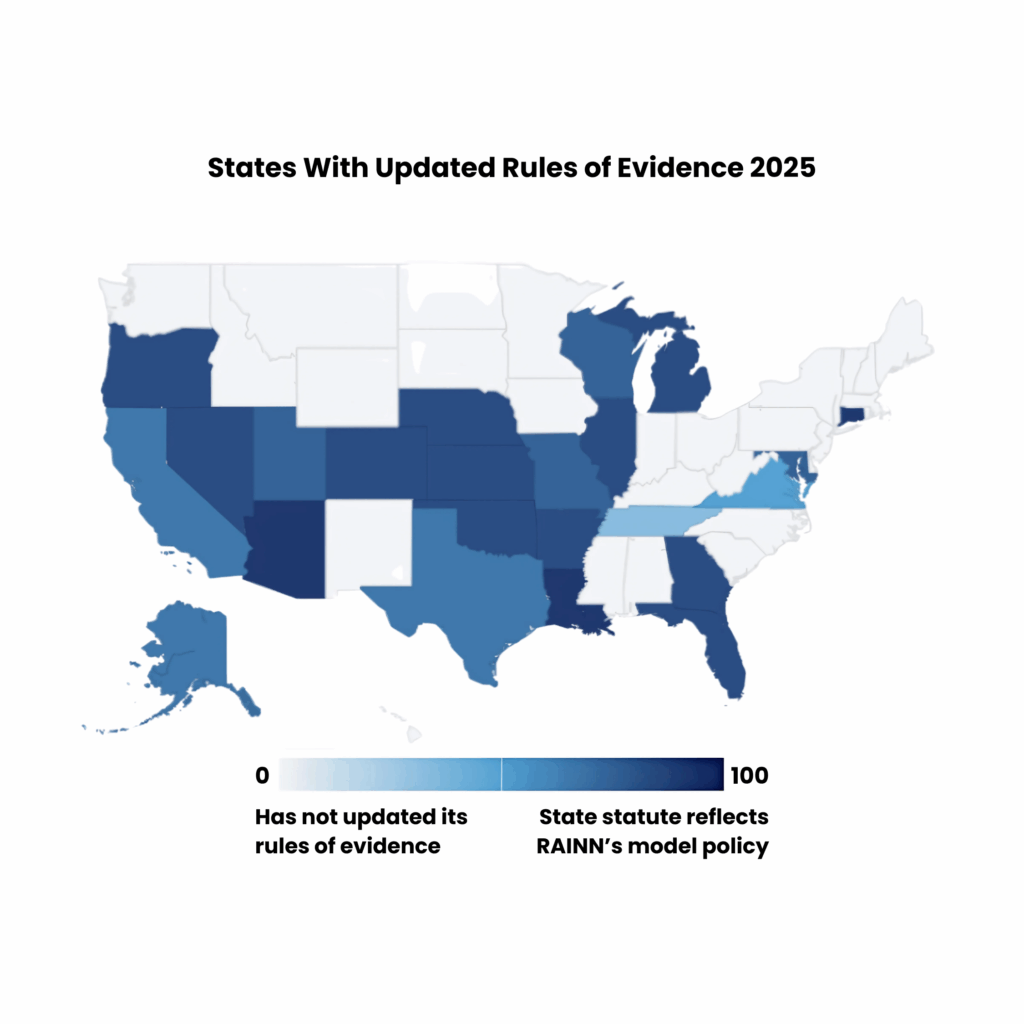

Twenty-three states have already changed their rules of evidence for cases of sex crimes involving children, while 18 of those states have changed their rules of evidence for sex crimes involving both adults and children. The Federal Rules of Evidence, which have been upheld as constitutional, allow this highly relevant evidence to be considered by juries in sexual assault trials. Survivors deserve to be heard and juries deserve to hear them.

Below we explain the need for this reform, outline the constitutionality of modifying the rules of evidence, provide considerations for legislators and their staff, and offer model text to modify state statutes.

Courts Leave Survivors Alone in Their Fight For Justice

Every 74 seconds,

someone in the U.S. is sexually assaulted. Every nine minutes, that someone is a child.1Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, 2019–2022.

See More Facts & StatisticsSexual assault pervades our communities, but ingrained rape myths and fear often hide it. Due to the historically high underreporting of sexual assault, the true number of assaults is likely much higher. Many survivors feel alone, fear not being believed when they report, or think nothing will result if they do. (1)

Of the reported cases, an even smaller fraction see a day in court. Approximately five to twenty forcible rapes out of 100 will be reported to law enforcement, and “0.4 to 5.4 will be prosecuted.” (2) Few cases make it to the courtroom.

Victims of sexual assault face the ordinary and appropriate burdens of proof that apply in other criminal cases; yet they often find their testimony devalued because of the same biases and inequalities that led them to be targeted for sexual assault in the first place. Perpetrators often commit sexual offenses behind closed doors, where no surveillance cameras or third-party eyewitnesses can provide corroboration. Instead, corroboration can and should come from other victims, who can shed light on the context of the crime. Without this evidence, survivors face undue and extreme pressure on their testimony of the crime.

Victims of other crimes do not face the rape myths and pervasive biases generated by victim blaming that survivors do. (3) These assumptions follow the survivor into the courtroom, if they make it that far. Even survivors whose accounts are corroborated find themselves disbelieved. (4) Furthermore, survivors of sexual assault often face forms of cross-examination and character assassination, both in and out of court, that are laced with misogyny, racism, and other biases. (5)

Attrition through the justice process benefits perpetrators, who often repeat their crimes. Approximately one-third (35.7%) of defendants in a sample of offenders identified by DNA through sexual assault kits had two or more sexual assaults linked via DNA. This is higher than what is typically documented (8-15%) in court records. (6) Survivors of sexual assault may not know that their assailant has a pattern of behavior, contributing to their isolation in seeking justice.

When perpetrators are brought to court, prosecutors are often hindered by rules of evidence that prevent them from presenting all the relevant evidence necessary for the jury to determine, beyond a reasonable doubt, whether the crime was committed. For a jury to consider a single act without this context is to continue to benefit those already empowered by an unequal justice system.

Juries Are Prevented From Carrying Out Justice

Juries of your state cannot carry out justice without access to evidence of prior sexual conduct.

To illustrate the true nature of a sexual assault and counteract biases and outdated understandings of rape, prosecutors need all the evidence of the crime available to them. However, as shown in Figure 1, at least 27 states preclude prosecutors from introducing crucial evidence of the defendant’s credibility and understanding of the victim’s consent. In these states, the brave survivor enters the courtroom to give evidence without any of the perpetrator’s history to contextualize their testimony. This survivor stands alone, even when the evidence exists to show the rapist was aware the victim lacked consent

Lacking all context and evidence available, these juries make decisions that threaten public safety, fail victims, and unfairly gauge a defendant’s guilt. Without evidence of other relevant criminal sexual conduct, the prosecution cannot use a valid tool to assess the defendant’s credibility. Without this evidence, the court ignores how sexual assault is committed and perpetuated. By allowing for the admissibility of the relevant evidence, legislation correcting the rules of evidence supports juries in carrying out justice by helping them understand the real-life situation of a serial predator who has committed the act repeatedly, rather than an isolated incident

Aligning Rules of Evidence Supports Fair Jury Decisions

Sexual assault cases require that the jury understand whether the defendant knew or should have known the victim’s lack of consent. The crucial concept of consent distinguishes sexual assault cases from other violent crimes. The jury can never convict just because they committed crimes in the past, but a defendant’s past behavior can help a jury understand how to interpret the facts in a sexual offense case. Our justice system convicts people for their actions, not their character. Changing the rules of evidence to include other relevant sexual conduct supports this by providing the jury with the full context of the crime while protecting the right to a fair trial. Changing the rules of evidence helps juries uncover the truth.

To determine the facts and allow the jury to understand the nature of consent in the case, the prosecution must prove the intent and state of mind of the defendant. Without the proposed rules of evidence, the prosecution cannot always admit evidence that would assist the jury in determining the vicitms credibility when it comes to what happened. With the proposed rules, however, a jury can consider prior sexual conduct of the defendant to determine the veracity of the victim and the defendant.

How It Can Play Out in Court

For example, let’s say the defendant (let’s call him John) used to be in a relationship with a woman (let’s call her Sarah). At one point in their relationship, John initiated sexual intercourse with Sarah despite her repeated protests that she didn’t want to have sex. Afterward, Sarah sent John a text telling him she was upset because he forced himself on her. Later, John hung out with his buddies and told them about the disagreement, and one of his friends told him it’s not cool to ignore someone’s refusal to have sex.

Years later, John is in court because another woman he’d been seeing (Jane) accused him of rape. He says it was consensual sex, and that she’s lying. John chooses not to testify but his lawyer attacks the victim and her credibility by claiming, “This is a unique incident. How could he possibly have known that this was rape? Just because she says so? She’s lying.” Without the updated rules of evidence, the prosecutor cannot bring in the texts from the ex-girlfriend or the friend who admonished John’s behavior before.

In this example, the jury won’t know that John has been told before that his behavior is unacceptable and amounts to rape, and therefore should have known that a woman saying no to sex was rape. The jury views the incident with no context. The jury might agree with John that the victim lies. With the updated rules, however, the prosecution can call another witness and introduce evidence to testify that John is not credible when he says there’s no way he could have known his behavior wasn’t ok. This evidence also backs up Jane, rebutting that she is a liar. Introducing relevant sexual conduct informs the jury on how the defendant perceived the victims’ actions and helps the jury determine the facts of the case.

This is not a new concept. This proposal is modeled after Rule 413 of the Federal Rules of Evidence. According to FRE 413, in a criminal case in which a defendant is accused of sexual assault, the court may admit evidence that the defendant committed any other past sexual assault on any matter to which it is relevant.

Constitutional Solutions

In 1995, Congress changed the Federal Rules of Evidence to include Rule 413 (sexual assault cases) and Rule 414 (child molestation cases). These federal rules allow a court in sexual offense cases to admit a defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct “on any matter to which it is relevant.” This includes the defendant’s propensity to commit the sexual offense. These rules created a presumption that any evidence relevant to the charged sexual offense is admissible. (7)

Federal courts held these rules were constitutional and “a prosecutor may use evidence of prior sexual assaults precisely to show that a defendant has a pattern or propensity for committing sexual assault.” (8) The United States Supreme Court has never ruled that propensity evidence alone violates the defendant’s fundamental right to a fair trial. (9) Admitting a defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct, even for propensity purposes, is constitutional, so long as the trial court ensures that the admitted evidence is not unfairly prejudicial. (10)

Courts recognize Congress had a legitimate purpose in admitting a defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct. The overall objective of these rules was “enhancing effective prosecution for sexual assaults.” (11) Congress believed that admitting this evidence would assist juries in assessing credibility. Congress knew that crimes of sexual violence “frequently involved victim-witnesses who are traumatized and unable to effectively testify.” (12) As Representative Bob Dole stated in support of these rules,

[S]exual assault cases, where adults are the victims, often turn on difficult credibility determinations. Alleged consent by the victim is rarely an issue in prosecutions for other violent crimes—the accused mugger does not claim that the victim freely handed over his wallet as a gift—but the defendant in a rape case often contends that the victim engaged in consensual sex and then falsely accused him. Knowledge that the defendant has committed rapes on other occasions is frequently critical in assessing the relative plausibility of these claims and accurately deciding cases that would otherwise become unresolvable swearing matches. (13)

Congress, courts, and even critics of these rules acknowledge that admitting relevant sexual conduct of the defendant is important in sexual offense cases, where too often the focus is on the victim instead of the defendant. (14) A defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct can corroborate the victim’s testimony. Evidence of relevant sexual conduct by the defendant reduces the impact of biases and rape myths on jurors. “Corroboratory information about the defendant [] limits the prejudice to the victim that often results from jurors’ tendencies to blame victims in acquaintance rape cases.” (15) An additional legitimate legislative purpose of Rule 413 is that it “encourages rape reporting and increased conviction rates by directing the jury’s attention to the defendant.” (16)

When the jury is considering the credibility of the witnesses, a defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct is important in assessing the defendant’s credibility. During trial, victims are frequently ridiculed for their actions during a sexual offense, and made to appear that their behavior is unique or unusual while the defendant’s behavior is “normal.” If the victim’s credibility is being attacked, then evidence of the defendant’s credibility should also be considered. Admitting a defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct presents the jury with the whole picture, which can impeach the defendant’s credibility. This important evidence should not be introduced only if the defendant chooses to testify. “It is no great stretch to permit the [impeachment] evidence to be introduced in the case-in-chief when defense counsel” is making the argument.” (17)

Every federal court and nearly every state court ruling on the constitutionality of a rule admitting a defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct has held that the rule is consistent with a defendant’s right to a fair trial. Courts recognize “the unique nature of sexual assault crimes”, the historical admission of propensity evidence in sexual assault cases, and the protections provided by other rules of evidence as reasons for admitting this important evidence.

5 Recommendations for Rules of Evidence

RAINN recommends the following to policymakers to admit evidence of the defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct in sexual offense cases while ensuring a fair trial for the victim and the defendant.

1. Create a Presumption of Admissibility

Create a presumption of admissibility for the defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct, including for purposes of propensity.

Nearly every state has a rule regarding character evidence that allows the admission of evidence of other crimes, wrongs, or acts that are relevant. However, these rules usually limit the admissibility of relevant evidence to certain circumstances and specifically exclude propensity evidence. As discussed above, the defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct in sexual offense cases is essential to credibility determinations, and admitting it for propensity purposes is permissible. The rule should allow any relevant evidence, including for propensity purposes.

Sample Statutory Language

In a criminal case in which the defendant is charged with a sexual offense, evidence of the defendant’s commission of other crimes, wrongs, or acts involving a sexual offense shall be admissible and may be considered on any matter to which it is relevant, including propensity.

2. Remove Admissibility Limitations

Admissible evidence should not be limited to incidents that only resulted in a conviction.

Sexual offenses are incredibly underreported. When someone is charged with a sexual offense, this sometimes draws attention to their actions and prompts other victims to come forward. One reason victims do not report is that they do not feel they will be believed, as it is often their word against the defendant’s. However, when they learn the defendant has other victims, they no longer feel alone and are more likely to come forward and disclose what happened. This uncharged conduct is relevant to assessing the credibility of both the victim and the defendant, rebuts claims of consent by the defendant, and “limits the prejudice to the victim that often results from jurors’ tendencies to blame victims.”

Sample Statutory Language

In a criminal case in which the defendant is charged with a sexual offense, evidence of the defendant’s commission of other crimes, wrongs, or acts involving a sexual offense….“ (see above)

3. Allow Evidence of Prior Relevant Sexual Conduct

Evidence of a defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct should be admitted in trials for sex offenses against children and adults.

The importance of relevant evidence in assessing credibility and countering victim-blaming is equally important to child or adult victims. When considering the cases in which the evidence is admissible, the rule should include those sexual offense cases that frequently occur outside the presence of witnesses or include a lack of consent as an element of the offense.

Sample Statutory Language

In this rule, “sexual offense” means any alleged violation of any offense in [chapter/title] involving sexual contact or sexually explicit conduct, or an equivalent offense of another state, the United States, or any foreign jurisdiction.

Crimes to consider including in the definition:

- Sexual assault/Rape

- Sexual abuse of a child/child molestation

- Sexual exploitation

- Human trafficking involving a sexual offense

- Incest

- Forcible sodomy

4. Exclude Unfairly Prejudicial Evidence

Explicitly state that the judge may exclude any evidence admitted under the rule if it would be unfairly prejudicial to the defendant.

Since the right to a fair trial is important for defendants and victims, evidence can still be excluded if it would result in an unfair trial. Most states already have rules that trial courts use to determine whether evidence is unfairly prejudicial. The new rule can incorporate those rules, or insert the language into the new rule. Another protection against unfair prejudice would be to include a requirement that the jury be instructed on the proper purpose of the prior relevant sexual conduct evidence.

Sample Statutory Language

(c) The court may exclude relevant evidence if its probative value is substantially outweighed by a danger of one or more of the following: unfair prejudice, confusing the issues, misleading the jury, undue delay, wasting time, or needlessly presenting cumulative evidence.

OR

(c) Admission of evidence under paragraph (a) is subject to Rule [403] of the [insert State] Rules of Evidence. This rule does not limit the admission or consideration of evidence under any other rule.

(d) In cases in which evidence is admitted under this rule, the court shall instruct the jury as to the proper use of such evidence.

5. Ensure Time for Analysis by the Court

Require notice of a prosecutor’s intent to admit the defendant’s prior relevant sexual conduct to ensure courts can analyze the issue in advance of trial.

A judge needs to carefully evaluate whether a defendant’s prior sexual conduct is admissible under the rule. Best practices should encourage this analysis to be done in advance of the trial. Providing certainty to victims on whether they will have to testify and prepare for any restrictions the court may impose on their testimony will reduce the anxiety and trauma for those victims.

Sample Statutory Language

(e) The prosecution must notify the defendant or defense counsel in writing of the intent to offer evidence under this rule in accordance with Rule [insert notice requirements, usually contained in a rule related to admissibility of character evidence].

OR

(e) If the prosecutor intends to offer evidence under this rule, the prosecutor must file notice with the court and disclose to the defendant evidence intended to be introduced, including any reports, statements of witnesses, or a summary of the substance of any testimony that the prosecuting attorney expects to offer. The prosecutor must do so at least 45 days before trial or at a later time that the court allows for good cause. The defendant shall make disclosure as to rebuttal evidence offered under this rule no later than 20 days after receipt of the state’s disclosure or at such other time as the court may allow for good cause.

Model Standalone Bill for Rules of Evidence

Most states can use the above statutory text to incorporate or modify their existing rules. If lawmakers prefer a standalone bill, however, we offer model legislation below.

Sample Bill Language

If the prosecutor intends to offer evidence under this rule, the prosecutor must file notice with the court and disclose to the defendant evidence intended to be introduced, including any reports, statements of witnesses, or a summary of the substance of any testimony that the prosecuting attorney expects to offer. The prosecutor must do so at least 45 days before trial or at a later time that the court allows for good cause. The defendant shall make disclosure as to rebuttal evidence offered under this rule no later than 20 days after receipt of the state’s disclosure or at such other time as the court may allow for good cause.

In a criminal case in which the defendant is charged with a sexual offense, evidence of the defendant’s commission of other crimes, wrongs, or acts involving a sexual offense shall be admissible and may be considered on any matter to which it is relevant, including propensity.

In this rule, “sexual offense” means any alleged violation of any offense in [chapter/title] involving sexual contact or sexually explicit conduct, or an equivalent offense of another state, the United States, or any foreign jurisdiction.

Admission of evidence under paragraph (a) is subject to Rule [403] of the [insert State] Rules of Evidence. This rule does not limit the admission or consideration of evidence under any other rule.

In cases in which evidence is admitted under this rule, the court shall instruct the jury as to the proper use of such evidence.

Next Steps

- Visit RAINN’s State Law Database for information about the laws in your state

- Learn about statutes of limitations for sexual violence cases

- Email policy@rainn.org to schedule a call with a RAINN policy expert

NOTES & CITATIONS

(1) Murphy-Oikonen, J., Chambers, L., Miller, A., & McQueen, K. (2022). Sexual Assault Case Attrition: The Voices of Survivors. Sage Open, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221144612

(2) Lonsway, K. A., & Archambault, J. (2012). The “Justice Gap” for Sexual Assault Cases: Future Directions for Research and Reform. Violence Against Women, 18(2), 145-168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212440017

(3) https://www.ourresilience.org/what-you-need-to-know/myths-and-facts/

(4) Murphy-Oikonen J, McQueen K, Miller A, Chambers L, Hiebert A. Unfounded Sexual Assault: Women’s Experiences of Not Being Believed by the Police. J Interpers Violence. 2022 Jun;37(11-12):NP8916-NP8940. doi: 10.1177/0886260520978190. Epub 2020 Dec 11. PMID: 33305675; PMCID: PMC9136376.

(5) Huhtanen, H. (2022). Gender Bias in Sexual Assault Response and Investigation. Part 1: Implicit Gender Bias. End Violence Against Women International. https://evawintl.org/wp-content/uploads/TB-Gender-Bias-1-4-Combined-1.pdf Monahan, Jerald, and Sheila Polk. “The Effect of Cultural Bias on the Investigation and Prosecution of Sexual Assault.” Policechiefmagazine.org, Police Chief Magazine, 2021, www.policechiefmagazine.org/the-effect-of-cultural-bias-on-the-investigation/.

(6) Campbell, R., Feeney, H., Goodman-Williams, R., Sharma, D. B., & Pierce, S. J. (2020). Connecting the dots: Identifying suspected serial sexual offenders through forensic DNA evidence. Psychology of Violence, 10(3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000243

(7) Concerns that this evidence would prolong cases or require additional evidence are addressed by existing rules of evidence that allow a judge to exclude evidence that would cause undue delay, waste time, or present cumulative evidence.

(8) United States v. Schaffer, 851 F.3d 166, 178 (2d Cir. 2017)

(9) U.S. v. Enjady, 134 F.3d 1427, 1431 (10th Cir.1998)

(10) United States v. Schaffer, 851 F.3d 166, 180 (2d Cir. 2017).

(11) U.S. v. Enjady, 134 F.3d 1427, 1434 (10th Cir.1998)

(12) Id.

(13) 140 Cong. Rec. S129901–01, S12990 (R. Dole, Sept. 20, 1994) U.S. v. Enjady, 134 F.3d 1427, 1431 (10th Cir.1998)(quoting).

(14) U.S. v. Enjady, 134 F.3d 1427, 1432 (10th Cir.1998)(quoting M. Sheft, Federal Rule of Evidence 413: A Dangerous New Frontier, 33 Am.Crim. L.Rev. 57, 69-70 (1995))

(15) Id.

(16) Id.

(17) U.S. v. Enjady, 134 F.3d 1427, 1433 (10th Cir.1998)

Last updated: August 28, 2025